Simpósio em San Diego

A State University de San Diego organizou, em abril, um Simpósio sobre o Brasil, onde foram debatidos temas atuais como as cidades e os grandes eventos esportivos, as recentes manifestações de 2013, com cunho mais reivindicativo e as atuais, de cunho mais político partidário, dentre outros temas.

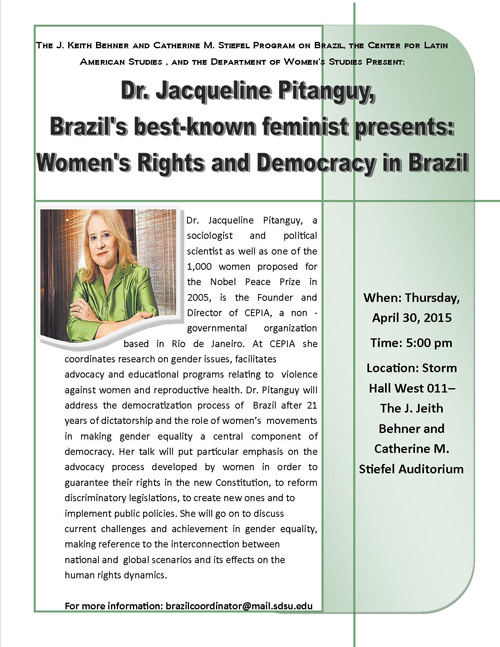

Jacqueline Pitanguy foi convidada a falar sobre sua jornada enquanto feminista e ativista pelos direitos humanos das mulheres desde o início desse percurso,nos anos setenta até os dias atuais, ressaltando avanços, barreiras e desafios em sua caminhada.

Veja a apresentação de Jacqueline onde ela narra diferentes momentos de sua vida enquanto feminista

Symposium

SDSU

University of San Diego

April 30 2015

Jacqueline Pitanguy

Thank you so much for the invitation to participate at this symposium .I am very happy to have the opportunity to share with you my journey as a feminist and human rights activist in Brazil and to point out some of the main challenges that we still face.

I am part of a generation of Latin Americans that lived their high school and their college years under military dictatorship, a generation that moved from one to another country in the south cone of the continent, in a kind of political Diaspora. There is gain and loss in this Diaspora. The major gain, besides being alive, is to feel that you have played a role, that you were not a passive spectator of history. The lost is of those who did not make the journey with you, that died on the way.

I was in Chile, as a student of sociology when Salvador Allende was elected president. I lived through the euphoria of believing in the possibility of a socialist democratic regime in South America and through the despair of the end of this dream. As a Brazilian, I had experienced , while still in school, the 1964 coup d’état in my own country that overturned a democratically elected government. This coup occurred in the context of cold war between the USA and the Soviet Union and the fear that communism might rule in Latin America. For 21 years, with different degrees of violence and coercion, Brazil lived under a dictatorship in a context characterized by a divorce between the state and civil society.

These were years of suppression of basic civil rights like habeas corpus, freedom of association, freedom of the press, free elections and consequently of intense anti dictatorship mobilization by civil society. At that time, however, women’s rights were not included in the political agenda. I am part of a group of women who placed women’s rights in that agenda. That is when I began my feminist journey. Back to Brazil I was working as a researcher in the department of sociology at the Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro; I came across the deep inequalities of women’s in the labor force. I was analyzing census data and I still remember the impact of that statistical evidence and the urge to better understand and do something about women’s discrimination in Brazil. My peers were deeply involved with the struggle for the democratization of the country and gender inequality was not an issue but I found a group of women who were asking the same questions. Together we started Grupo Ceres, one of the first feminist groups in the country. That’s when domestic and sexual violence; sexuality and reproductive rights; and gender discriminations in legislation, in the labor market, in education and in political life became central issues for my view of a just and democratic society.

We can distinguish different contexts in Brazilian contemporary history, the periods of dictatorship, of transition and of democracy. Under dictatorship, which lasted for 21 years, feminism inaugurated its presence at the public scenario as a political actor, questioning the power relations, inequalities and hierarchies that defined first and second class citizens in our society. We worked in alliance with the social forces that were struggling against the authoritarian regime, and expanded the democratic agenda, demanding that the concept of democracy include equal rights for women as a central value. While united in our struggle against the military rule, some of the groups with whom we shared the democratic opposition , perceived us as diversionists’, in the sense that they considered that it was not the moment to propose a women´s rights agenda . But we persevered certain that there is no democratic agenda with first and second class citizens.

The other moment refers to the period after the election of the first civilian president in 1985 until the promulgation of the 1988 Constitution, with a democratic context in place. By then, I was a mother of three children , a girl and two boys, living with my husband a Chilean economist, in Rio de Janeiro. I had already some visibility as a feminist activist, and was doing a Ph.D. at São Paulo University, which meant commuting. I had also published, in co-authorship, three books that dealt with women’s condition, from different angles: women in the labor market, sexuality and social identity and feminism as a political movement.

Life was hectic, and I was moved by the inebriating feeling of being part of a movement in which we shared dreams, plans and fears. 1985 was a key year in my life as a civil rights and women’s rights activist. While celebrating the fact that finally we had a civilian president, I was part of a group of women who demanded the creation of a national organization that would have authority, administrative autonomy and budgetary allocations available to counsel the presidency on women’s issues, and to propose and implement federal public policies and legislation.

The campaign to create a National Council on Women’s Rights was waged in the context of Brazil’s re-democratization and the occupation of federal executive power by sectors, which had been held at bay for more than two decades. The National Council for Women’s Rights was created in August 1985, by a congressional law. From that moment until 1989, my life was deeply connected with this organization as I experienced a new path in my feminist journey. I have headed CNDM for four years, working together with activists who embarked in the challenge of advancing the feminist agenda from within the state. This organ played a key role in assuring women´s rights in the new Federal Constitution that was enacted in 1988. The campaign A Constitution to be worth has to guarantee women´s rights is considered one of the most successful advocacy process for gender equality in the country, with the inclusion in our Magna Carta, of the majority of women’s demands regarding labor and social rights and benefits , social security, family relations, reproductive rights, property rights , violence.

My memories as the president of this new governmental organ, holding a cabinet position, are filled with feelings of deep joy over our victories and of anguish over difficult moments. I moved to Brasilia, the capital of the country and was able to bring with me a large and diverse group of women, deeply committed and dedicated to a common cause. We supported each other because we knew that our time was not measured by a regular clock; our minutes were measured by a political watch. Would we have enough time to guarantee women’s rights in the constitutional process that was in course? Would we have enough time and political strength to influence legislation and public policies on reproductive health, domestic and sexual violence, social and labor rights of working women, including rural and domestic workers? Would we be able to change family laws that still placed men as the head of the family? Could we influence the education of boys and girls so they would reject sexual stereotypes? Would we have enough time to denounce racism and the situation of black women, enlarge maternal rights and struggle for free day care facilities for children?

The NCWR had no political history or tradition to support failures, no important economic interests to back it up, and our agenda was uncomfortable for many and dangerous for others, including the conservative and powerful sectors of the Catholic Church. Yet, we not only survived for more than four years but we became visible, strong and respected and contributed to significant advancements in women’s condition in Brazilian society. Our work guaranteed that 80% of women’s demands were included in the new constitution.

Going back over my memories of these years, it is hard for me to separate one specific moment or episode as being more significant than another because our gains in the constitution and in public policies were part of a process of mutual reinforcement that led to the improvement of women’s citizenship rights in many different areas. We organized our work with specialized departments dealing with themes such as reproductive health, violence, black women, legislation, women and labor including rural women, child-care support (nurseries and kindergartens), education and culture.

The main challenges presented to us came from the fact that we were dealing with deeply rooted gender power relations, sustained by laws, customs and values. To question the status of men as head of the family as defined in civil law and the need for a marriage certificate for the state to recognize a stable union as a family was difficult. To propose that the regulation of fertility be recognized as a citizen’s right and that the state had the duty to provide information on sexual and reproductive health and access to contraception was not an easy political platform at that time. We needed not only to have our proposals well grounded on solid data and juridical arguments but also to spend a lot of time in political negotiation inside the government.

I would like to briefly describe this advocacy process. CNDM started in 1995 a national campaign , visiting all the 26 states of the country, working in connection with local women´s groups to raise awareness in the importance of seizing the moment of the election of a new Congress, which would be responsible to elaborate the new democratic charter of the country, to incorporate women´s rights in it. The local movements were encouraged to organize consultative meetings with the various women’s groups, associations etc. and send to CNDM their proposals and demands for the new constitution . These suggestions came by thousands to our offices, by fax, letters, telegrams since the internet was not yet available. They were analyzed first by our own staff, to separate those who were absurd or out of place. The rest of the demands was then organized according to the charters of the constitution that were being debated in the Congress, and were analyzed by a pro bono group of lawyers and jurists committed to our cause. A huge conference, with representatives from NGOs and women’s movements from all over the country was organized by CNDM who presented this condensed version of the inputs received. A document called Letter of Brazilian Women to the Constituents was approved , and delivered to the Congress ¹. For the next 3 years, different advocacy tools such as constant visits with political parties leaders, massive pressure over parliamentarians organized by women’s movements from their local electoral basis, campaigns on TV and the written press , marches, folders distributed all over the country with our proposals, were used to lobby for the inclusion of women´s demands. In this process more than 100 amendments were sent by CNDM to the Constituent Assembly.

¹ Most of the Constitutions from after World War II are extensive and comprehend more dimensions of political, economical and social life.

There is not a linear path towards progress and rights are historical conquests subject to backlashes, paralysis and advances. The broader political context frames the limits and possibilities of the human rights struggle . There was a bitter taste in our astonishing victory in the Constitution. The history of Brazil shows the conservative elite’s capacity to organize and determine the direction of the state. These forces were already regrouping. For the next year, NCWR suffered all sorts of pressures from within the government, including budgetary cuts of 70%, coming particularly from the Ministry of Justice with the support of the president. Our achievements were uncomfortable for the federal government. From that point onwards, it was clear that the NCWR did not reflect the hegemonic tendency within the new configuration of state power. The crisis of the NCWR was part of the changes and rearrangements of political forces within the state.

The legitimacy the NCWR already enjoyed, the support that we received across the country, from women’s movements, trade unions and other civil society organizations, as well as from some progressive representatives in the national congress enabled us to remain in power till 1989, when myself, the members of the Board and most staff resigned. We knew that to remain would mean to be co-opted by the conservative forces. In my memoirs of this period of my life , I want to retain the sense of our accomplishments that have been important not only for Brazilian women, in terms of legislation and of the creation of instruments to develop public policies such as councils for women’s rights and special police stations for victims of domestic violence, DEAMS, but also to women in other Latin American countries, countries that were also undergoing processes of democratization, where I shared our experiences in bringing gender issues to the democratic agenda.

Back to civil society I started then another part of my feminist journey, founding in 1990, with a friend from the CERES Group, a nongovernmental organization, CEPIA, Citizenship Information Studies Action in Rio de Janeiro which is currently celebrating its 25 years of age. Working from a gender perspective and within a human rights framework, CEPIA focuses on issues of, sexual and reproductive health and rights, violence and access to justice. Advocacy is an important part of our agenda and we propose laws and evaluate public policies working both locally, at Rio de Janeiro’s state level, and nationally. We also invest in research and in education, promoting an Institute on women´s rights and working at the grass root level with women from low income communities.

The nineties were the decade in which women’s groups became more institutionalized through nongovernmental organizations (NGO’s) and networks of civil society organizations that played an important role in our national arena. This was also the decade of the internationalization of feminist advocacy work. There was a proliferation of transnational coalitions and networks developing campaigns, building common strategies, participating in international forums. The technological revolution in communications, still shy, facilitated however international interchanges between these networks, which played a key role at the UN conferences held during the nineties. Women became powerful actors in this arena, having played a particularly important role in the UN Human Rights Conference held in Vienna, 1993, and at the Cairo Population and Development Conference in 1994, when important paradigmatic shifts, such as the consideration of domestic violence as a human rights violation and the move from a demographic driven population approach to one based on the recognition of reproductive rights, were consolidated in Beijing’s Women’s Conference of 1995.

All through the nineties, I have been involved in this transnational dynamic. I feel that I am part of an international movement which is capable of building consensual agendas and strategies that cross cultures and countries. I also feel that, at the same time, we can only be truly international if we belong nationally, if we are deeply committed and involved with what goes on in our own country. The linkages between local and international are clear: the international commitments assumed by the Brazilian Government have always been a powerful instrument to undergird and sustain our national demands. On the other hand, we can only advance internationally if at the internal or national level if these international commitments are consolidated in national laws and programs.

As my feminist journey continues in this new century , or maybe not so new anymore, I am convinced that one of our main challenges is to build agendas that cut across different sectors and that it is urgent to deepen the dialogue with other civic society organizations in order to make gender equality a central issue of any democratic debate, not only a women’s activists issue. There is still a long way to go in that direction.

Making a retrospective of these decades of struggle for gender equality and women’s rights, I don´t see a linear path towards progress. Paralysis and backlashes pave the way. But the ground in which we walk is not the same. We do still face the crucial challenge of diminishing the gap between laws and reality, but women is not anymore a second class citizen in Brazil. Equal rights have been formally assured in legal terms. Legislations on family planning and on domestic violence regulate constitutional provisions and there are public policies in place to assure women´s rights.

However it is not a moment for celebrations. Because rights are historical conquests and they can be lost. We see now in the Brazilian scenario a new , strong political force: the Christian religious fundamentalism that threaten the sustainability, the implementation and the enlargement of such rights.

To understand the challenges we face it is important to pay attention to the fact that the agenda of feminism encompasses issues that are ranked differently in the scale of power and face different degrees of legitimacy , social acceptance and resistances, demanding specific strategies .The cultural patterns prevailing in a given society and internationally, as well as the political junctures, the dynamics among the actors such as governments, NGOs, religious authorities, the media, and other players in the political arena, have an effect on how a certain issue is ranked in laws and public policies.

Among the various issues of the feminist agenda I would like to distinguish two: violence against women and sexual and reproductive rights, that face different degrees of opposition and support in their political trajectory. In Brazil the advocacy work against VAW has advanced significantly . Besides services such as the Special Police Stations, close to 500 around the country, and shelters, the Secretaria de Politicas para as Mulheres, (SPM) is responsible for national plans to combat VAW that comprise a number of different initiatives, including the improvement of statistics, the training of security officers, the creation of services, inclusive in remote areas of the Amazon , the monitoring and evaluation of services in place. Brazil has, since 2006, a special law on VAW, The Maria da Penha law that deals with domestic violence in a broad sense, including psychological violence, stipulates protective measures for the victim , determines the creation of special justice courts for domestic violence crimes, among others measures. The advances in both laws and public policies on VAW are a success story in which CEPIA has been deeply involved.

The political trajectory of reproductive rights, abortion in particular, is not the same. While family planning is accepted and implemented by the government the legislation on abortion still dates from the 1940 and the interruption of pregnancy is only allowed in cases of rape and risk of life and even so is constantly threatened of backlashes. The advocacy context for such rights has always been very difficult and the field of allies and partners reduced. Feminists, with very few exceptions, are isolated in the struggle for decriminalization and regulation of the access to abortion.. The only advancement in enlarging the circumstances was the recent (2012) ruling of the Supreme Court allowing the interruption of the pregnancy in cases of a severe fetus mal formation incompatible with life.

The international context of growing religious fundamentalism with a conservative perspective on sexuality and reproduction, a growing presence of evangelical churches that, along with the ever present Catholic Church, play more and more a political role in the country responds, in great part for the paralysis and risk of backlashes that laws and public policies that would fully assure the reproductive rights face in the country. Only close to 60 services attend victims of rape, providing abortion and they are under constant pressure of the religious conservative forces.

So I finish my presentation by inviting all to be always on the move, always vigilant , knowing that activism, in its various forms, in the academia, in civil organizations, different associations and individually is key to keep the conquests, avoid backlashes and advance. And also to say that women are not an homogeneous category, that class, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation responds for important differences and inequalities among ourselves but that in spite of these differences, we are apolitical category with a heavy agenda in front of us.

I have not ended my feminist journey and with CEPIA we are working to monitor and evaluate the public policies in place in the area of VAW and to demand the full realization of sexual and reproductive rights. It is a never ending process…